STÄDTEBAULICHE PLANUNG FÜR ERBPLFEGE DENKMAL ERLANGEN

The English text is below.

Die Stadt und Stadtwanderer

„Walking is a way of engaging and interacting with the world, providing the means of exposing oneself to new, changing perceptions and experiences and of acquiring an expanded awareness of our surroundings. Through such experiences, and through a deeper understanding of the places we occupy, we acquire a better understanding of our own position in the world.“ [1]

Wir leben in der Stadt und mit der Stadt. Unser Leben, das sich aus verschiedenen Erinnerungen zusammensetzt, kommt ohne die Stadt nicht aus. Die Anwohner werden Teil des Stadtbilds und die Stadt als Hintergrund der Erinnerung ist immer Teil unseres Lebens. Die eigene Stadt zu beobachten und zu entdecken ist daher ein Prozess der Suche nach Identität.

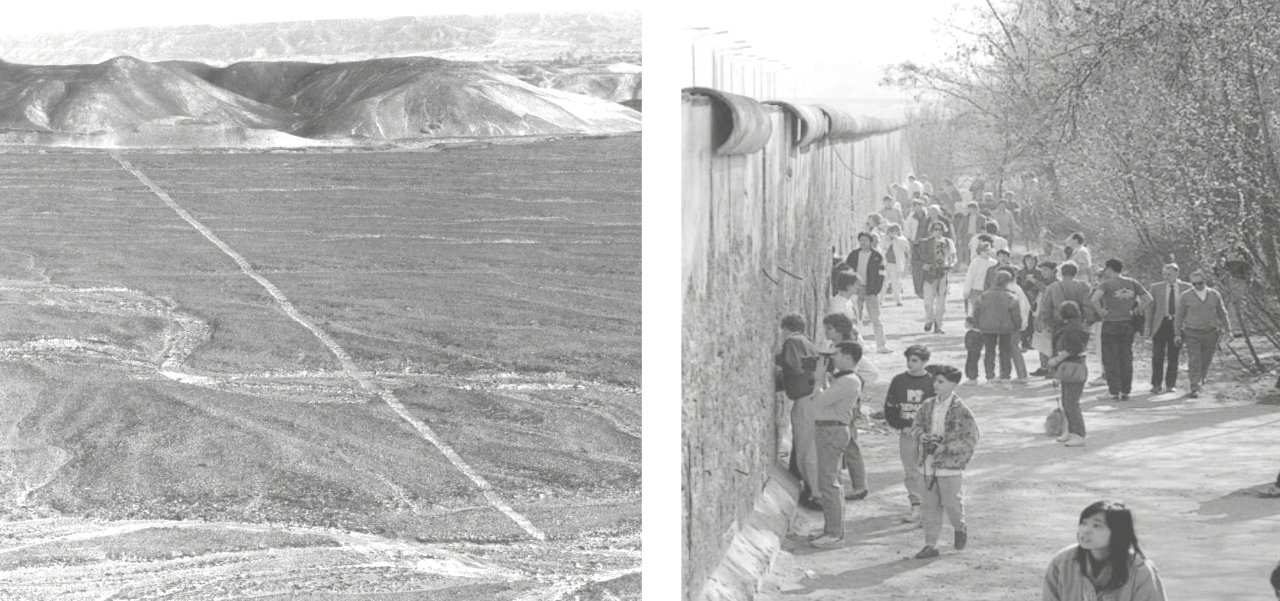

In der Anonymität der Menschenmasse werden die Spuren des Individuums von Zeit zu Zeit verwischt. Individualität besteht jedoch in der Art und Weise, wie wir die Stadt erleben. Wir flanieren ohne Zwang an vielen Orten der Stadt. Dabei reagieren wir nicht nur auf das Gegebene, sondern wir sind auf der Suche nach dem Unentdeckten, indem wir die Elemente der Stadt beobachten. Alle Elemente der Stadt und des städtischen Alltags, z.B. Geschäfte, Straßen, hinterlassene Spuren und Fußgänger, sind Objekte der Beobachtung. Die Entdeckung der Stadt geschieht im Augenblick und in der Bewegung des Stadtwanderers, im Gehen, im Flanieren, das nicht nur eine körperliche, sondern auch eine geistige Aktivität ist. Dabei bringt jeder Stadtwanderer sein eigenes Interesse und seine eigene Erinnerung an die Stadt zum Ausdruck. Der Stadtwanderer als Individuum will die verborgene Seite der Stadt freilegen.

Das Flanieren lässt sich daher mit „einer Art Lektüre“ (Franz Hessel) oder mit einer „Figur des Detektivs” (Walter Benjamin) vergleichen. Damit diese Entdeckungen nicht verblassen, müssen wir sie mit uns leben lassen, in unserer Zeit. Dazu ist es allerdings notwendig, dass die Orte uns einladen, sie zu begehen, denn der Weg, den die Orte zusammen bilden, wird noch in der Zukunft bleiben, auch wenn wir nicht mehr da sind, und die Erinnerungen in die Zukunft tragen.

Ph.D Yeonhee Yu

[1]Paul Moorhouse (2002)“ The intricacy of the skein, the complexity of the web: Richard long’s art, 2002 In: Richard Long, Walking the Line. Thames & Hudson, S.33.

Das Leben in der Zukunt, die jemandem genommen wurde

Edward H. Carr zufolge reflektiert Geschichte stets Gegenwart. Allein die Fragestellung über Geschehen in der Vergangenheit ist ein Teil der Antwort darauf, wie man gegenwärtige Probleme betrachtet. Solange das Jetzt andauert, werden sich Fragen bezüglich vergangener Geschehnisse nie erschöpfen.

Vor uns liegt ein Ort der Stadt Erlangen, an dem die Werte des damaligen Individuums mit seinem Leben gewaltsam ausgelöscht wurden. Es geht um die Frage, wie das lang verschwiegene Thema, NS-Medizinverbrechen an diesem Ort heute zum Klingen gebracht werden kann.

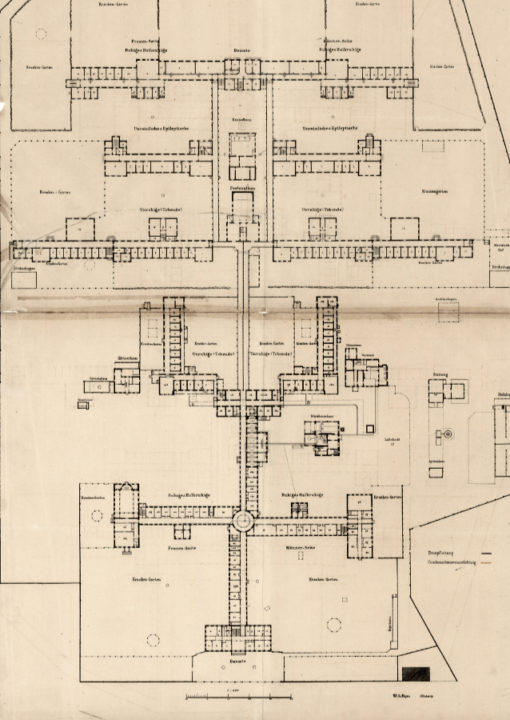

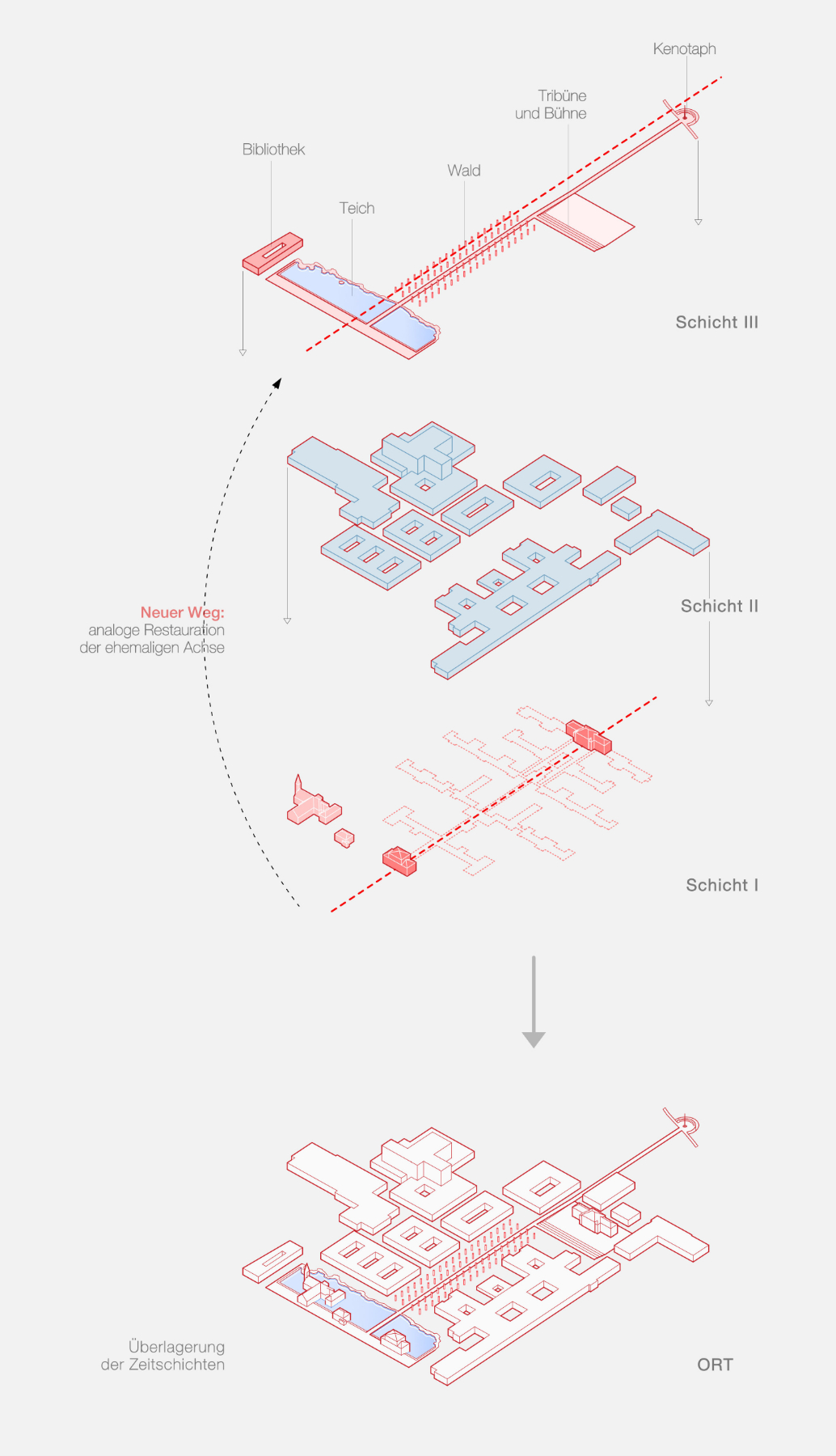

Eine Erinnerung, die das Geschehene so wiedergibt, wie es wirklich war, ist jedoch unmöglich. Was die Architektur hier zu leisten hat, ist nicht ein bloßer Reflex auf die Faktizität des historischen Ortes, sondern die Ermöglichung einer Erfahrung des Konflikts an diesem Ort. Dieser Konflikt besteht in der mehrfachen Überlagerung des Ortes. Der historische Ort mit dem Denkmal, der bestehende und sich erweiternde Klinikcampus und die alte Klinikachse konstituieren den Ort. Diese Überlagerungen gilt es zu durchdringen und die Geschichtlichkeit des Ortes zum Klingen zu bringen.

Um die Bedeutung des Ortes zu entdecken und dem Geschehen eingedenk zu sein, muss man sich einerseits fragen, was wir an diesem Ort, der von den Qualen der Opfer und den Verbrechen der Täter geprägt ist, dokumentieren, auch wenn nur wenige originale Gebäude erhalten sind. Andererseits müssen wir uns aber auch fragen, was wir an diesem Ort erleben. Es wird davon ausgegangen, dass die Geschichtlichkeit des Ortes durch das Flanieren der individuellen Stadtwanderer vertieft wird und die Besucherinnen sich über die Beschränkung auf eine bestimmte Zeit und einen bestimmten Ort hinaus an das Geschehene erinnern können müssen. Dieser Punkt wird an die Forderung der Praxis angeschlossen, dass der Ort den Besucherinnen die Erfahrung des Erwachens ermöglichen muss. An diesem Gedenkort werden die Besucherinnen nicht nur über die Brutalität der Verbrechen informiert, sondern auch mit der Tatsache konfrontiert, dass sie denselben Weg entlang gehen, welchen die Opfer hätten gehen können. Die innere Erschütterung, die die Besucherinnen erleben, macht es notwendig, sich selbst zu reflektieren und zu sensibilisieren. Wir sind uns bewusst, dass wir in der Zukunft leben, die den Opfern genommen wurde. Dabei ist es erlebbar, dass wir eine bestimmte Zukunft vorwegnehmen und bereits in ihr leben, nicht nur durch unsere Taten, sondern auch durch die Art und Weise wie wir der Vergangenheit gedenken.

Diese Erfahrung der Individuen bewahrt künftig diesen Ort als gesellschaftliche Stütze, an dem man über die zeitgenössische Ethik nachdenkt, diese überprüft, und gegebenenfalls Missstände aufdeckt. Zudem lädt der Ort die Bürger*innen zur konstruktiven Diskussion ein.

Miya Nakamura

research work investigator of post war interpretation

Städtebauliche Idee

Das Ziel des Projektes ist es, durch die Neuordnung des städtebaulichen Plans, ausgehend von den Anforderungen der Erlanger Bürger*innen, einen Ort zu schaffen, der das historische Bewusstsein widerspiegelt.

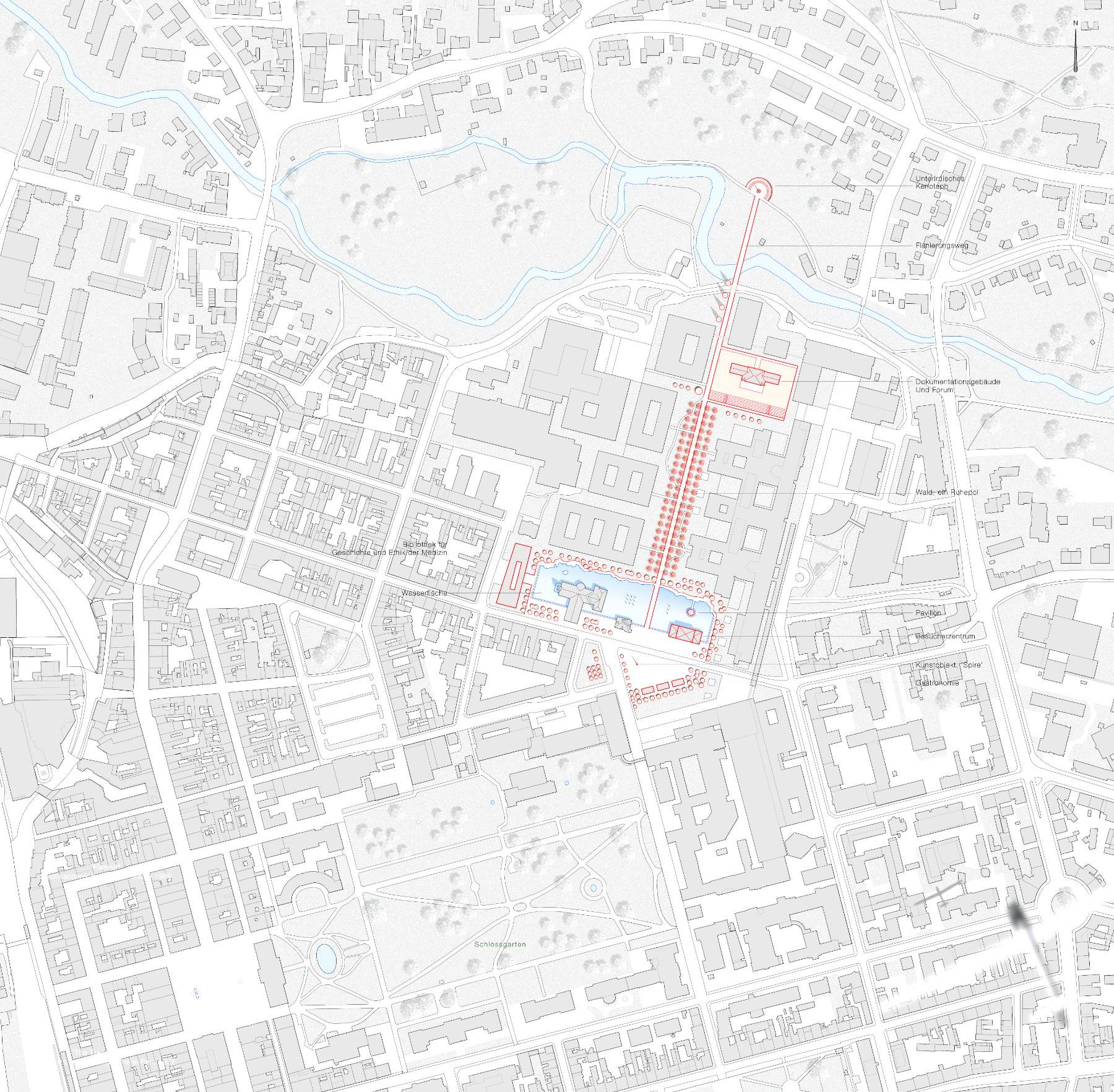

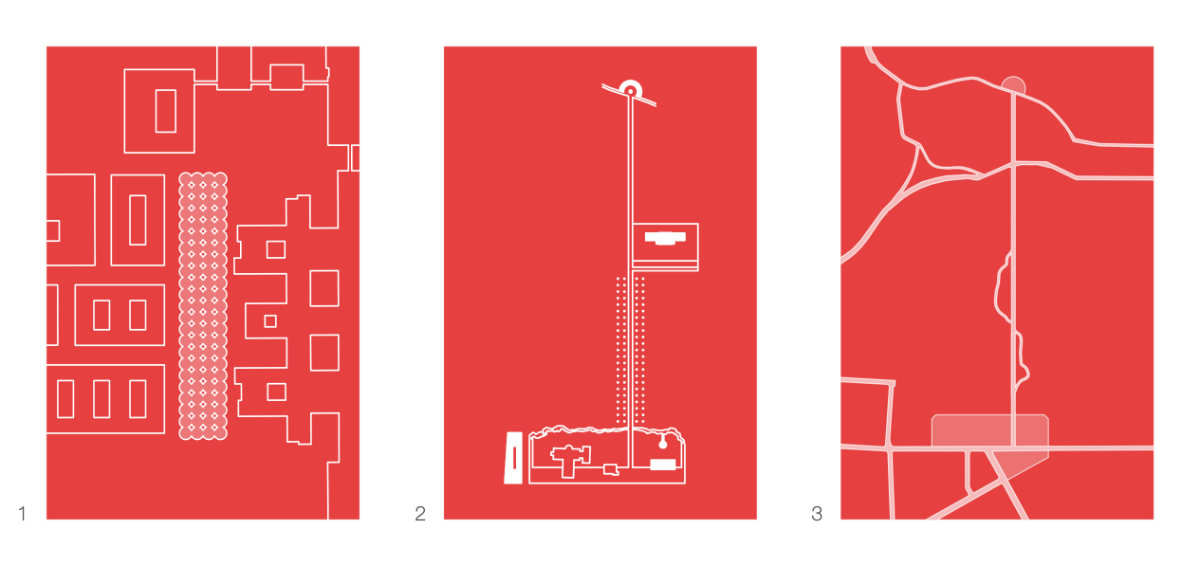

Dazu werden drei Stadträume und ein Verbindungsweg als Mittel zur Erschließung vorgeschlagen. Erstens, die Wasserfläche am Maximiliansplatz, wo sich das Besucherzentrum befindet. Zweitens, der Waldraum als Innenhof des Campus des Universitätsklinikums mit dem Forum. Drittens, das Kenotaph am Übergangsbereich zum Wohngebiet der Nordstadt

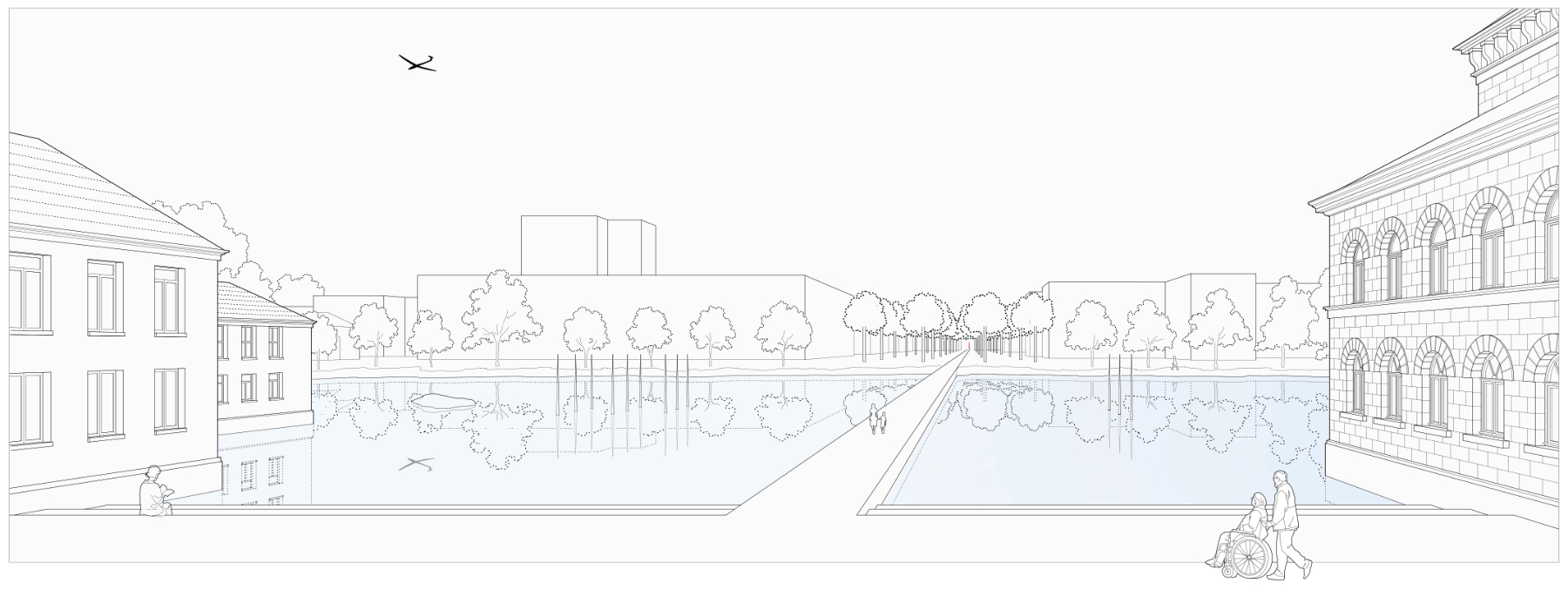

Der Maximiliansplatz ist ein Knotenpunkt, an dem drei Straßen enden und zwei Stadtraster zusammentreffen, und hat die große Chance, zu einem wichtigen Punkt in Erlangen zu werden. Hier wird die große Wasserfläche geplant, die sich von der Umgebung abhebt. Die Offenheit des großen Wasserraumes lädt als Eingang das Kollektiv der Massengesellschaft ein und bietet gleichzeitig einen qualitativen Erholungsraum zum freien Atmen und Entspannen.

Der Wasserraum bietet eine kontemplative Atmosphäre, in der sich Geschichte und Leben begegnen. Die drei Objekte, nämlich das Besucherzentrum, die Radiologie und Kirchengebäude bilden gemeinsam die Kontur der Wasserfläche und charakterisieren den Wasserraum. Die Bibliothek, die als aktiver Erinnerungsspeicher erwartet wird, grenzt an den Stadtraum an und bildet mit den umgebenden Bäumen die sanfte Landschaft des Ortes. All diese Elemente spiegeln sich mit unserer Verpflichtung, die Geschichte kritisch zu reflektieren, in der Wasserfläche wider.

Im Innenhof der Kliniken wird der Waldraum gestaltet. Dieser Wald hat einen anderen Charakter als die offenen Stadträume wie der Schlossgarten oder der Wasserraum am Maximiliansplatz. Mitten in der belebten Stadt ist dieser Wald ein Ruhepol, der den Spaziergang in eine tiefe Ruhe einleitet. Der Waldraum liegt im Zentrum des Campus Klinikums und bietet den qualitätsvollen Innenhof des Klinikums. Darüber hinaus stellt er die funktionale Erschließung zwischen Ost und West sowie Nord und Süd sicher.

Am Ende des Waldes trifft man auf das Forumsgebäude, umgeben von modernen Klinikgebäuden. Das denkmalgeschützte Bestandsgebäude wird durch eine Bühne und eine Tribüne ergänzt, die für Veranstaltungen im Freiraum zur Verfügung stehen. Das Forumsgebäude soll über die Frage nach einer bestimmten Tat oder Epoche hinaus für offene und aktive Diskussionen und öffentliche Veranstaltungen im medizinethischen Bereich nutzbar sein.

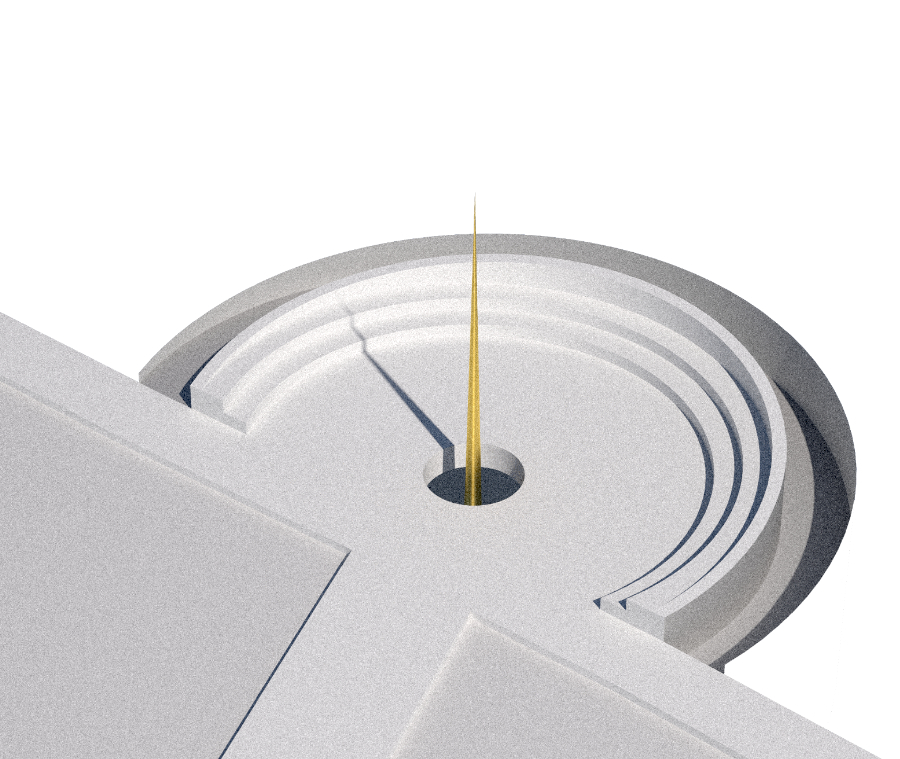

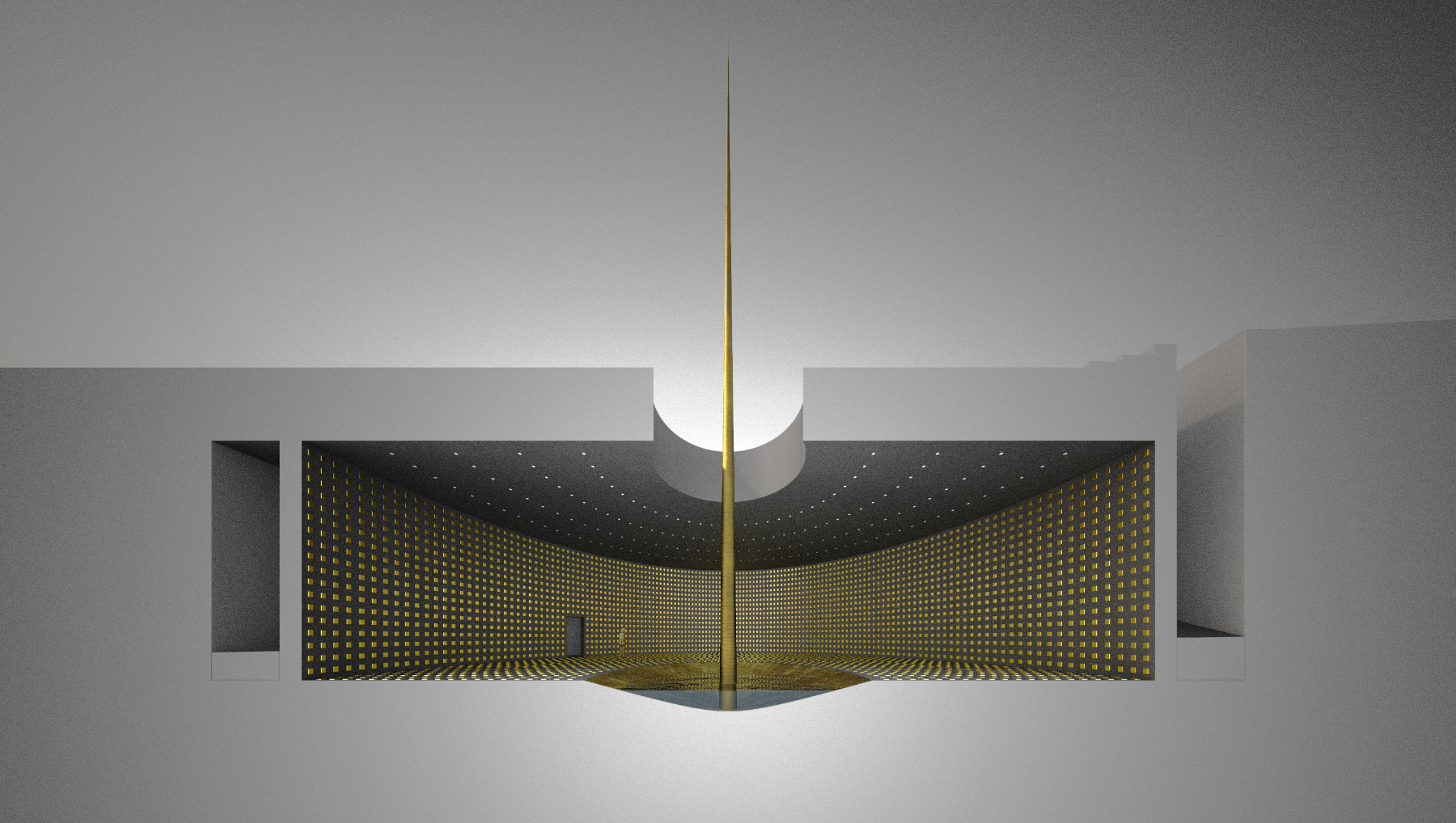

Auf der nördlichen Freifläche wird oberirdisch ein kleines Amphitheater und unterirdisch ein Kenotaph angelegt. Das Kenotaph erhält auf dem Dach einen Oculus, der die räumliche Verbindung zur Erde herstellt. Der unterirdische Raum wird mit unbeschrifteten Stolpersteinen umgegeben, die die Opfer der Medizinverbrechen und ihre gewaltsam zerstörte Zukunft symbolisieren.

The City and The City Walker

„Walking is a way of engaging and interacting with the world, providing the means of exposing oneself to new, changing perceptions and experiences and of acquiring an expanded awareness of our surroundings. Through such experiences, and through a deeper understanding of the places we occupy, we acquire a better understanding of our own position in the world.“ [1]

We live in the city, and with the city. Our lives, composed of various memories, cannot do without the city. Residents become part of the cityscape, and the city, as the backdrop of memory, is always a part of our lives. Observing and discovering our own city is therefore a process of searching for identity.

In the anonymity of the urban crowd, the traces of the individual are occasionally blurred. However, individuality exists in the way we experience the city. We stroll without constraint in many places within the city. In doing so, we not only react to what is given but also seek the undiscovered by observing the elements of the city. All elements of the city and urban daily life, such as shops, streets, left traces, and pedestrians, are objects of observation. The discovery of the city happens in the moment and in the movement of the urban walker, in walking, in strolling, which is not only a physical but also a mental activity. Each urban walker expresses their own interest and memories of the city. The urban walker as an individual seeks to uncover the hidden side of the city.

Thus, flaneur can be compared to ‘a kind of reading’ (Franz Hessel) or to a ‘detective figure’ (Walter Benjamin). To ensure that these discoveries do not fade, we must keep them alive with us, in our time. However, it is necessary for the places to invite us to walk them because the path formed by these places will remain in the future, even when we are no longer here, carrying memories into the future.

Ph.D Yeonhee Yu

[1]Paul Moorhouse (2002)“ The intricacy of the skein, the complexity of the web: Richard long’s art, 2002 In: Richard Long, Walking the Line. Thames & Hudson, S.33.

Our Lives as Someone’s Stolen Future

According to Edward H. Carr, history always reflects the present. Merely questioning past events is a part of the answer to how we perceive current problems. As long as the present continues, questions regarding past events will never be exhausted.

Before us lies a place in the city of Erlangen where the values of individuals of that time were violently extinguished. The question is how the long-silenced topic of Nazi medical crimes at this location can be brought to life today.However, a memory that accurately reflects what happened is impossible. What architecture must accomplish here is not merely a reflection of the historical site’s factual history but the creation of an experience of conflict at this location. This conflict arises from the multiple layers of the site. The historical site with the memorial, the existing and expanding clinic campus, and the old clinic axis constitute the location. These layers need to be penetrated to bring out the historical significance of the site.

To discover the significance of the site and to be mindful of what happened there, one must, on the one hand, consider what we can document at this location, even though only a few original buildings remain. On the other hand, we must also think about what we can experience at this location. It is assumed that the historical significance of the site is deepened by the act of individuals strolling through it, and visitors must be able to remember what happened beyond the limitation of a specific time and place. This point is linked to the demand that the site must enable visitors to experience awakening. At this memorial site, visitors are not only informed about the brutality of the crimes but also confronted with the fact that they are walking the same path that the victims could have walked. The inner turmoil that visitors experience necessitates self-reflection and sensitization. We are aware that we live in the future that was taken from the victims. It is palpable that we anticipate a certain future and already live in it, not only through our actions but also through how we remember the past.

This individual experience will preserve this place as a societal support for considering contemporary ethics, evaluating them, and potentially exposing wrongdoing. Moreover, the site invites citizens to engage in constructive discussion.

Miya Nakamura

research work investigator of post war interpretation

Architectural Idea

The aim of the project is to create a place that reflects historical awareness through the reorganization of the urban plan based on the requirements of the citizens of Erlangen. To achieve this, three urban spaces and a connecting pathway are proposed as means of development:

The water area at Maximiliansplatz, where the visitor center is located.

The forested area as the courtyard of the University Hospital campus with the forum.

The cenotaph at the transitional area to the residential district of Nordstadt.

Maximiliansplatz is a hub where three streets converge, and it has a great potential to become a significant point in Erlangen. Here, a large water area is planned, distinct from its surroundings. The openness of the extensive water space invites the collective of mass society while providing a quality space for relaxation, breathing freely, and unwinding.

The water space offers a contemplative atmosphere where history and life intersect. The three objects, namely the visitor center, radiology, and church building, together delineate the contour of the water area and characterize the aquatic space. The library, expected to serve as an active memory repository, adjoins the urban space and forms the gentle landscape of the site with the surrounding trees. All these elements are a reflection of our commitment to critically reflect on history within the water surface.

In the courtyard of the clinics, the forested area is designed. This forest has a different character compared to the open urban spaces like Schlossgarten or the water space at Maximiliansplatz. Situated in the bustling city, this forest serves as a place of tranquility that initiates a deep sense of calm during a walk. The forested area is located at the heart of the University Hospital campus, providing a high-quality inner courtyard for the campus. Additionally, it ensures functional connectivity between the east and west as well as the north and south.

At the end of the forest, you encounter the forum building, surrounded by modern clinic buildings. The protected historical building is complemented by a stage and a grandstand available for events in the open space. The forum building is intended to be used for open and active discussions and public events in the field of medical ethics, extending beyond specific acts or eras.

Above ground, a small amphitheater is constructed on the northern open space, while an underground cenotaph is created. The cenotaph features an Oculus on its roof, establishing a spatial connection to the earth. The underground space is enclosed by unmarked stumbling stones symbolizing the victims of medical crimes and their violently destroyed future.